Researchers Predict Age of T Cells to Improve Cancer Treatment

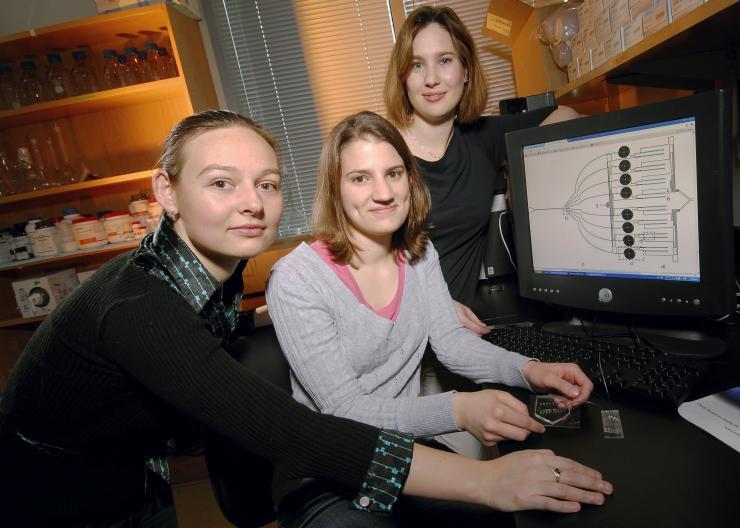

Georgia Tech engineers Catherine Rivet, Abby Hill and Melissa Kemp (left-right) display a diagram of the microfluidic device they used to assess T cells. The drawing illustrates the channels used to measure signaling events. (Credit: Gary Meek)

Manipulation of cells by a new microfluidic device may help clinicians improve a promising cancer therapy that harnesses the body's own immune cells to fight such diseases as metastatic melanoma, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia and neuroblastoma.

The therapy, known as adoptive T cell transfer, has shown encouraging results in clinical trials. This treatment involves removing disease-fighting immune cells called T cells from a cancer patient, multiplying them in the laboratory and then infusing them back into the patient's body to attack the cancer. The effectiveness of this therapy, however, is limited by the finite lifespan of T cells -- after many divisions, these cells become unresponsive and inactive.

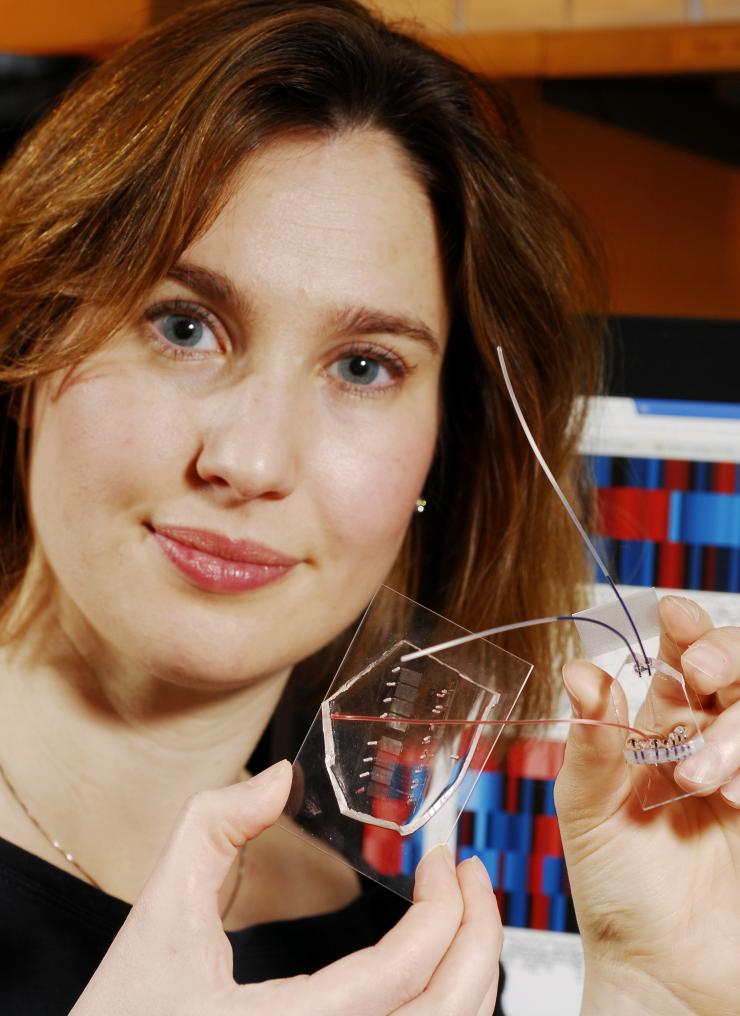

Researchers at Georgia Tech and Emory University have addressed this limitation by developing a microfluidic device for sample handling that allows a statistical model to be generated to evaluate cell responsiveness and accurately predict cell "age" and quality. Being able to assess the age and responsiveness of T cells -- and therefore transfer only young functional cells back into a cancer patient's body -- offers the potential to improve the therapeutic outcome of several cancers.

"The statistical model, enabled by the data generated with the microfluidic device, revealed an optimal combination of extracellular and intracellular proteins that accurately predict T cell age," said Melissa Kemp, an assistant professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory University. "Knowing this information will help facilitate the clinical development of appropriate T cell expansion and selection protocols."

Details on the microfluidic device and statistical model were published in the March issue of the journal Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, Georgia Cancer Coalition, and Georgia Tech Integrative Biosystems Institute.

Currently, clinicians measure T cell age by using multiple assays that rely on measurements from large cell populations. The measurements determine if cells are exhibiting functions known to appear at different stages in the life cycle of a T cell.

"Since no one measurement is a perfect predictor, it is advantageous to concurrently sample multiple proteins at different time points, which we can do with our microfluidic device," explained Kemp, who is also a Georgia Cancer Coalition Distinguished Professor. "The wealth of information we get from our device for a small number of cells far exceeds a single measurement from a population the same size by another assay type."

For their study, Kemp, electrical engineering graduate student Catherine Rivet and biomedical engineering undergraduate student Abby Hill analyzed CD8+ T cells from healthy blood donors. They acquired information from 25 static biomarkers and 48 dynamic signaling measurements and found a combination of phenotypic markers and protein signaling dynamics -- including Lck, ERK, CD28 and CD27 -- to be the most useful in predicting cellular age.

To obtain biomarker and dynamic signaling event measurements, the researchers ran the donor T cells through a microfluidic device designed in collaboration with Hang Lu, an associate professor in the Georgia Tech School of Chemical & Biomolecular Engineering. After stimulating the cells, the device divided them into different channels corresponding to eight different time points, ranging from 30 seconds to seven minutes. Then they were divided again into populations that were chemically treated to halt the biochemical reactions at snapshots in time to build up a picture of the signaling events that occurred as the T cells responded to antigen.

"While donor-to-donor variability is a confounding factor in these types of experiments, the technological platform minimized the experimental data variance and allowed stimulation time to be precisely controlled," said Lu.

With the donor T cell data, the researchers developed a model to assess which biomarkers or dynamical signaling events best predicted the quality of T cell function. The model found the most informative data in predicting cellular age to be the initial changes in signaling dynamics.

"Although a combination of biomarker and dynamic signaling data provided the optimal model, our results suggest that signaling information alone can predict cellular age almost as well as the entire dataset," noted Kemp.

In the future, Kemp plans to use this approach of combining multiple cell-based experiments on a microfluidic chip to integrate single-cell information with population-averaged techniques, such as multiplexed immunoassays or mass spectrometry.

This project is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)(Grant No. R21CA134299). The content is solely the responsibility of the principal investigator and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Research News & Publications Office

Georgia Institute of Technology

75 Fifth Street, N.W., Suite 314

Atlanta, Georgia 30308 USA

Media Relations Contacts: Abby Robinson (abby@innovate.gatech.edu; 404-385-3364) or John Toon (jtoon@gatech.edu; 404-894-6986)

Writer: Abby Robinson

Biomedical engineering professor Melissa Kemp shows the microfluidic device for sample handling that allowed a statistical model to be generated to evaluate T cell responsiveness and accurately predict cell age and quality. (Credit: Gary Meek)

Images of the microfluidic device developed at Georgia Tech to help researchers predict T cell age and quality in order to improve a type of cancer therapy called adoptive T cell transfer. (Credit: Gary Meek)